Just as the Greek Pantheon displayed an aura of architectural sophistication, the London Pantheon would become a symbol of higher-class entertainment. Few other places in London would come to be so well with the exclusive nature of the upper class.

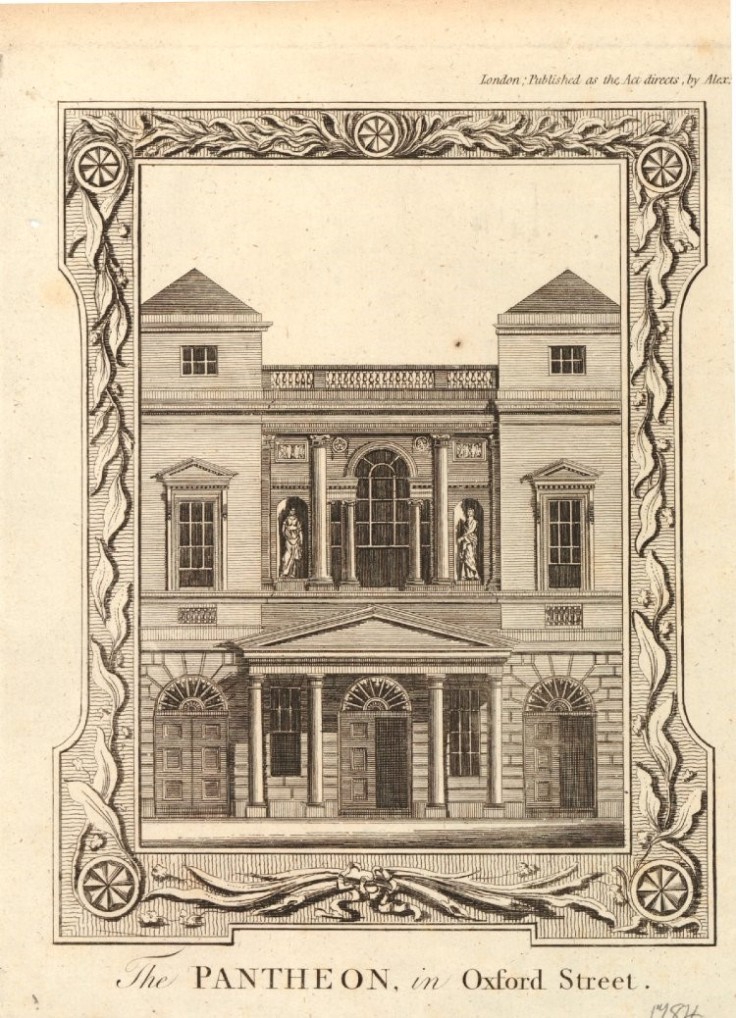

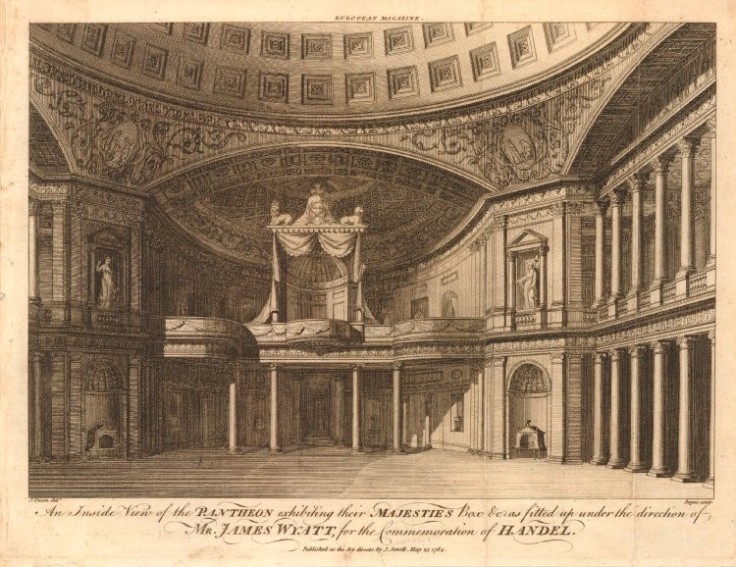

Designed by James Wyatt in 1772, the Pantheon was originally constructed as a place of entertainment, where balls, concerts, and masquerades would be held. It was called the Pantheon as it featured a large dome that was reminiscent of the Santa Maria Pantheon in Rome. The Pantheon’s main shape was two long rectangles. The north-most rectangle contained two parallel corridors separated by card rooms. The second rectangle was the main rotunda, with a side entrance to Poland Street.

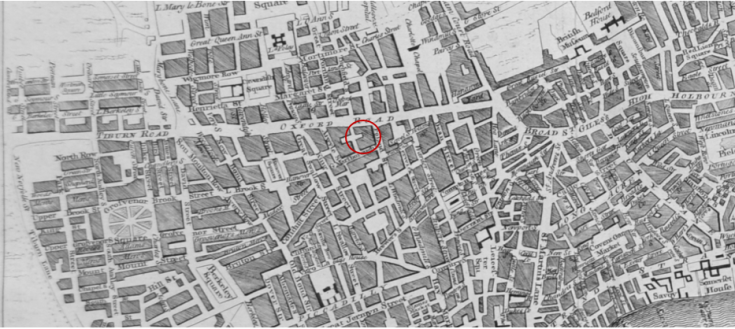

The London Pantheon was built on the corner of Oxford Street and Poland Street. In its approximate current location is the “Marks and Spencer Pantheon,” which is a department store.

The design of the Pantheon was so well received that it is regarded as one of the buildings that made James Wyatt one of the best-known architects of the Gothic Revival, and Romanticism movements.

In the story, Evelina writes in her 23rd letter “I was extremely struck with the beauty of the building, which greatly surpassed whatever I could have expected or imagined. Yet it has more the appearance of a chapel than of a place of diversion; and, though I was quite charmed with the magnificence of the room, I felt that I could not be as gay and thoughtless there as at Ranelagh; for there is something in it which rather inspires awe and solemnity, than mirth and pleasure.” The building’s Gothic style heavily employed the extravagance and detail of combining traditional roman architecture with medieval exuberance and was noted by many that it was one of the most beautiful buildings in London.

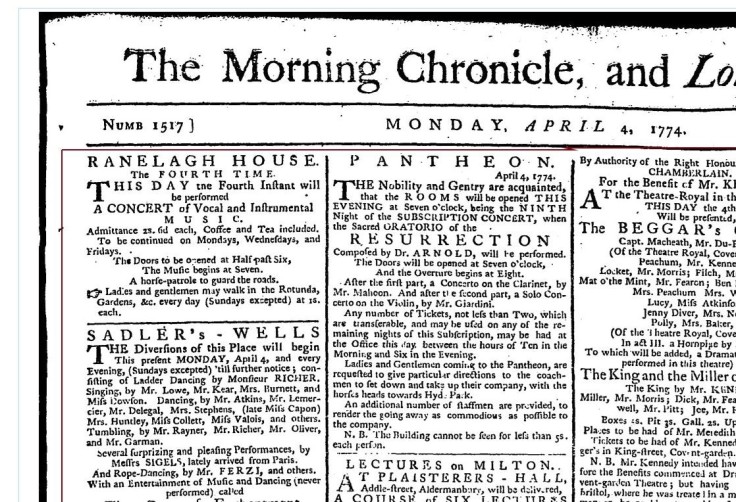

The admission price was half a guinea per person. However, guests would need a recommendation by a peeress to gain entry, effectively weeding out most people. Due to the exclusivity of the location, the traditional views of Pantheon patrons were that they were all upper class and well connected.

Within the context of Evelina, the Pantheon is another location where upper-class people in a small social circle will gather to entertain and be entertained. Evelina is brought here as a part of her indoctrination to high class culture. The true purpose of many of the early Pantheon events was to create a space where the upper class could socialize without the interference of the lower classes. In letter XXIII, Evelina wrote “There was an exceeding good concert, but too much talking to hear it well. Indeed I am quite astonished to find how little music is attended to in silence; for, though every body seems to admire, hardly any body listens.” Similar to other entertainment events, the true purpose as shown by Evelina’s commentary is to socialize, and not actually observe the event. Evelina being brought here is a way that her company is trying to keep her within the upper-class social circle.

Among the company that was with Evelina, it was only the upper class who accompanied Evelina to the event. The Mirvan family, Mrs. Duval, Sir Clement Willoughby, and Mr. Lovel were present, and all are gentry or aristocratic characters of the story. The lack of the presence of lower-class characters emphasizes the exclusivity of the location.

The Pantheon was not a profitable venture, as the extremely exclusive admission made it very difficult to be maintained effectively from a financial stance. Eventually, the theatre burned down and was rebuilt as an opera house in 1792, with less exclusive standards.

Burney has selected the Pantheon because the readers would immediately associate it as one of the most exclusive and expensive locations for the connected upper class to socialize without the presence of the lower classes.

Aaron Iwinski (Washington & Jefferson College)

Works Referenced

Burney, Fanny. Evelina or The History of a Young Lady’s Entrance Into the World. Norton Library ed., W.W. Norton and Company, 1965

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “James Wyatt.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 31 Aug. 2018

“Pantheon, The.” Survey of London: Volumes 31 and 32, St James Westminster, Part 2. Ed. F H W Sheppard. London: London County Council, 1963. 268-283. British History Online. Web. 1 December 2018.

Russell, Gillain. “The Peeresses and the Prostitutes: The Founding of the London Pantheon, 1772.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts, vol. 27, Taylor and Francis Group, 2005, pp. 11–30.

Stephen. “The Pantheon – a Place for the All the Gods in Oxford Street.” Footprints of London, 13 Feb. 2014,